Lyme Hall

The Legh (pronounced Lee) family of Lyme Hall got rich thanks to the Battle of Crécy in 1346, and stayed rich till the current day by keeping their heads down and avoiding trouble.

In the Wars of the Roses they were Yorkists till the Battle of Bosworth when they became Lancastrians. In the Reformation they were publicly protestant and privately catholic. In the Civil War the head of the family was too young to have opinions. After they Restoration they were royalists. In fact the future James II spent three months in this bedroom…

… shagging this mistress.

The only time the Leghs nearly got into trouble was after the Glorious Revolution when they remained staunchly Jacobite. After three months of listening to James II shagging the family probably counted him as a close personal friend. However, after the second time the head of the family was (unsuccessfully) prosecuted for high treason he gave up on politics and lived out his life in peace.

The line almost ended with this chap…

… who had no legitimate heirs, but as he had spent the last years of his life impregnating all the local serving wenches he had plenty of bastards to choose from. An act of parliament legitimized a couple of them, and this guy inherited the estate.

His name, after the act of parliament, was Thomas Legh. Thomas was an enthusiastic grave robber, or archeologist as he liked to be known. The library is decorated with classical greek tomb carvings.

It took another act of parliament for Thomas to get married. His future wife, heiress Ellen Turner, was abducted at the age of fifteen from boarding school. She was tricked into marrying her abductor, Edward Gibbon Wakefield, at Gretna Green in Scotland, and then taken to France. Gibbon (you don’t mind if I call him Gibbon, do you? I know it’s only his middle name, but you don’t meet people called Gibbon very often, and there are two in this story.) Anyway, Gibbon was hoping that Ellen’s father would accept the marriage and cough up some cash, as the mother of his first wife had done. But the Turners were made of sterner stuff.

Ellen’s father sent his lawyer to France and he returned with the girl. An act of parliament was required to annul the marriage, and Gibbon went to prison for three years. Ellen was free to marry Thomas Legh two years later, and die in childbirth two years after that. Gibbon went on to have a distinguished political career, promoted the colonization of Australia and New Zealand, and was mentioned by Karl Marx in Das Kapital. Thomas Legh remarried, had the house remodeled in the fashionable Italian style and stayed out of trouble.

The only reason that the abduction was against the law was that Ellen was an heiress. The law was there to protect property and not women.

The interiors are mostly 18th and 19th century with some older bits that date back to the Tudor origins of the building.

The severed arm holding a banner is a reference to the Battle of Crécy. The Black Prince’s banner was lost to the French, and Sir Thomas Danyers was one of the English soldiers who got it back by hacking off the arm of the Frenchman who was holding it. His granddaughter married a Legh. It’s such a shame it’s pronounced Lee and not Leg or I could be making jokes about the arm and the legs.

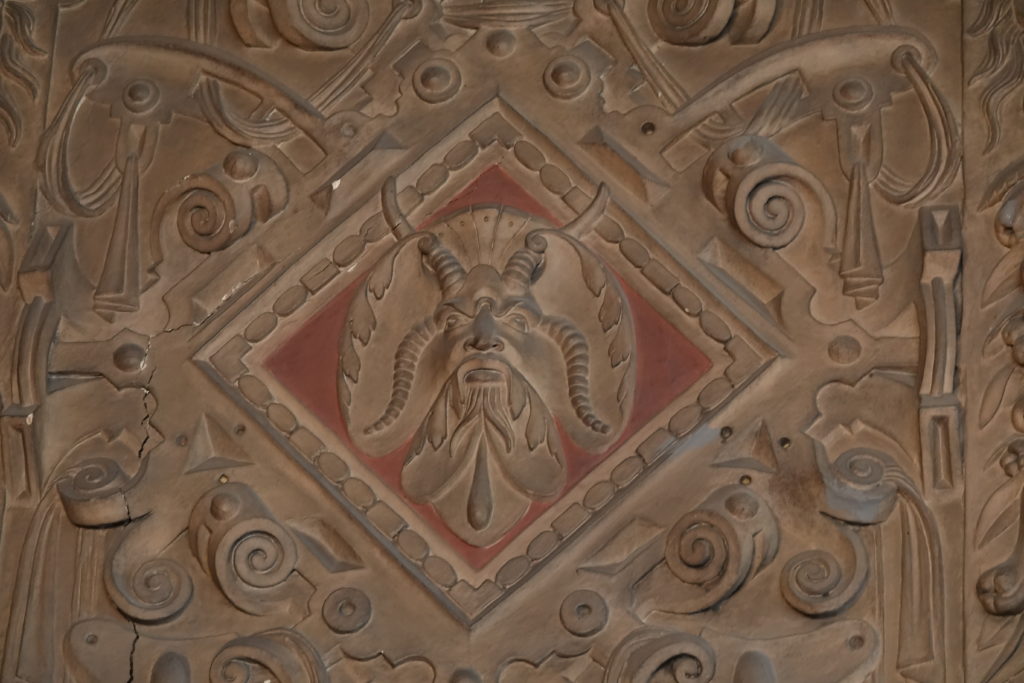

These weird faces are probably a survival from the 16th century. Nobody knows what they are.

This horse is looking pretty goofy…

… probably as a result of the three months it spent watching James II shagging.

The long gallery.

The saloon has wood carvings by Grinling Gibbons (see, I promised you another Gibbon).

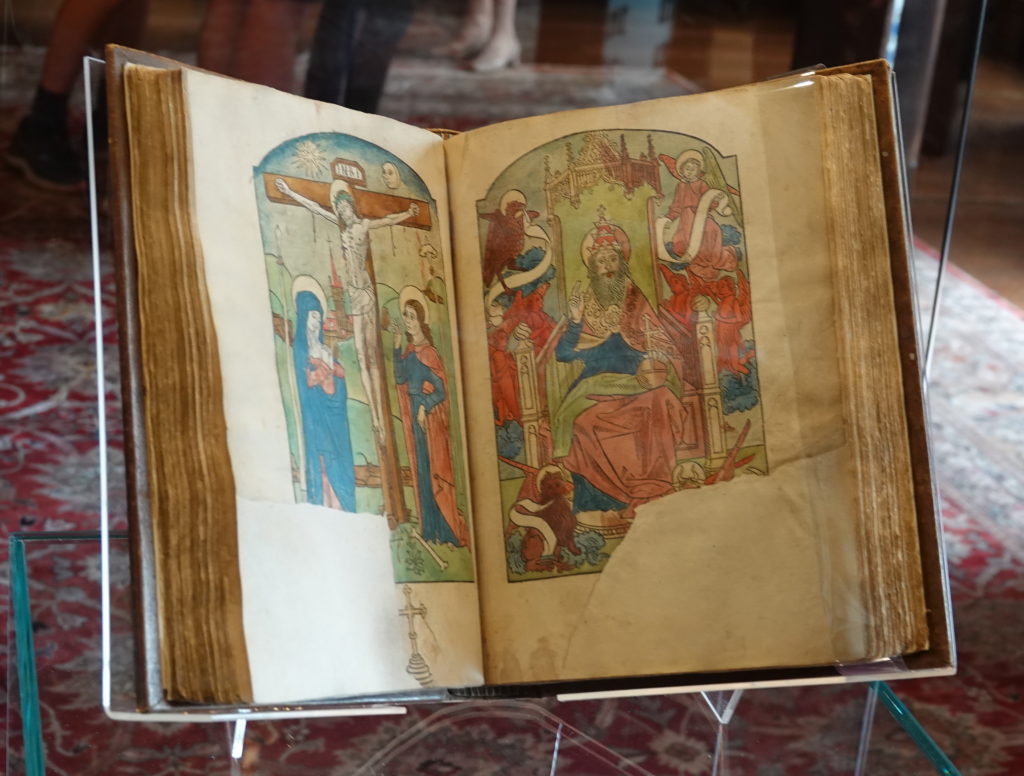

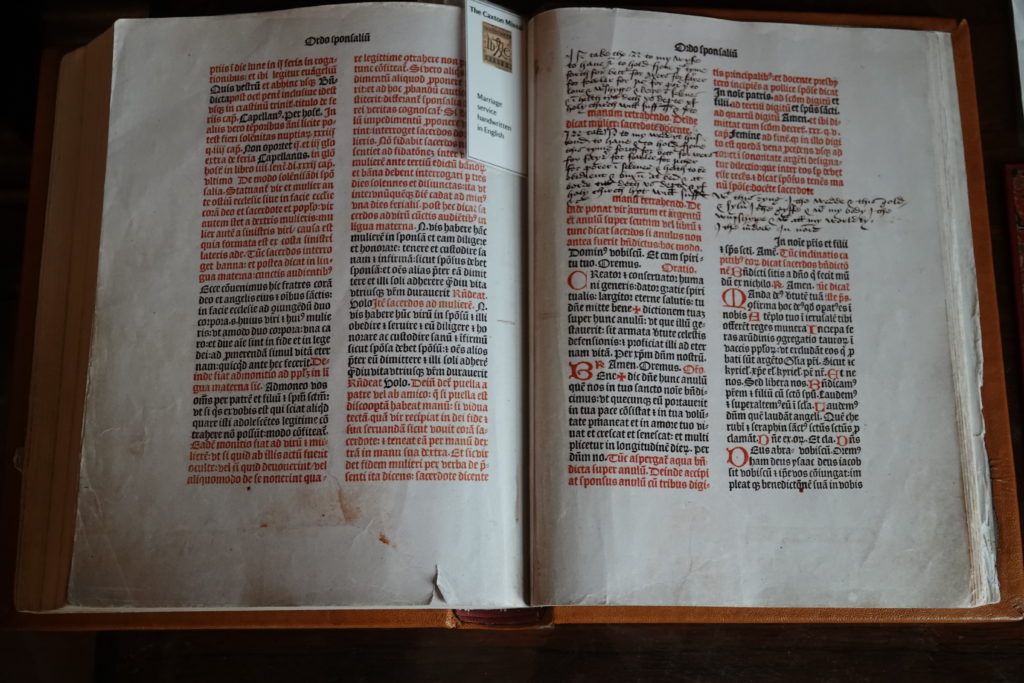

But the great treasure of Lyme Hall is a Caxton first edition, the only surviving copy of the Sarum Missal, which has been in the Legh family from the time it was first published until the National Trust bought it ten years ago. Though Caxton published it, he did not actually print it. Missals required two colors, black for what the priest said, and red for what he did, and Caxton did not know how to do this, so he went to a printer in Paris to print the book, and then published it with his imprint. Unfortunately the page that the book is currently open at shows the hand colored wood block prints, and not the two color printing.

So, to see the two color printing you’ll have to make do with a facsimile.

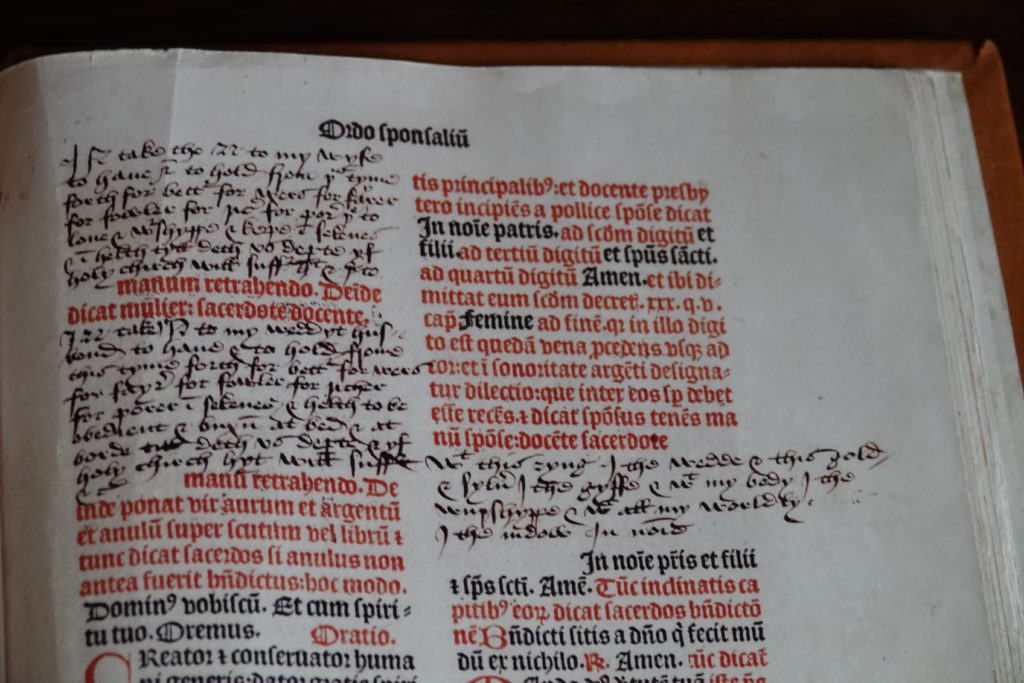

You may notice that some of it is hand written. Those are the marriage vows, which were in English. Caxton thought he could trust the French printers to get the Latin mass right, but not the English marriage vows.

You will notice that the wife had to promise, “to be obedient and buxom at bed and at borde”. I can see that he might not have wanted to let the French know about that.

The gardens include formal beds…

… an orangery…

… a rose garden…

.. and my favorite, the Italian garden.

At about eight hundred feet above sea level it is the second highest garden owned by the National Trust, and the high walls on two sides help to shelter it and provide extra sunlight.

It was a mile and a half trek each way though fields of sheep to get up there, but well worth the hike.

One thought on “Lyme Hall”

That grave relief is of an Athenian comic poet; it’s sometimes been thought to be Aristophanes, though as most of his contemporaries also died at some point the odds are rather against it. If it’s him it’s our only contemporary portrait, but the full head of hair is at odds with his self-described baldness. (Also, we’re fairly sure the real Aristophanes had a nose.)