The Irritation Game, Or How The Post Office Saved The Day

If you’ve seen the movie The Imitation Game, please be aware that it is a work of fantasy, and that the truth was much stranger and more wonderful. Alan Turing was not the only genius working at Bletchley, the Bombe was not the only, or even the best code breaking machine, and the Enigma code was not the most difficult code that was broken there. Benedict Cumberbatch is still cool, though.

It’s a three minute train ride from Fenny Stratford to Bletchley Park, which would be really convenient if the trains ran more than once an hour. In fact, since the massive and massively screwed up timetable change a couple of weeks ago we are lucky to have trains at all. Anyhow, I carefully timed my train and got to Bletchley Park just as the National Museum of Computing was opening. Some museums have grand buildings, with an architectural style reflecting the highest human aspirations, or at least the wealth of the donors. This one is a bunch of sheds.

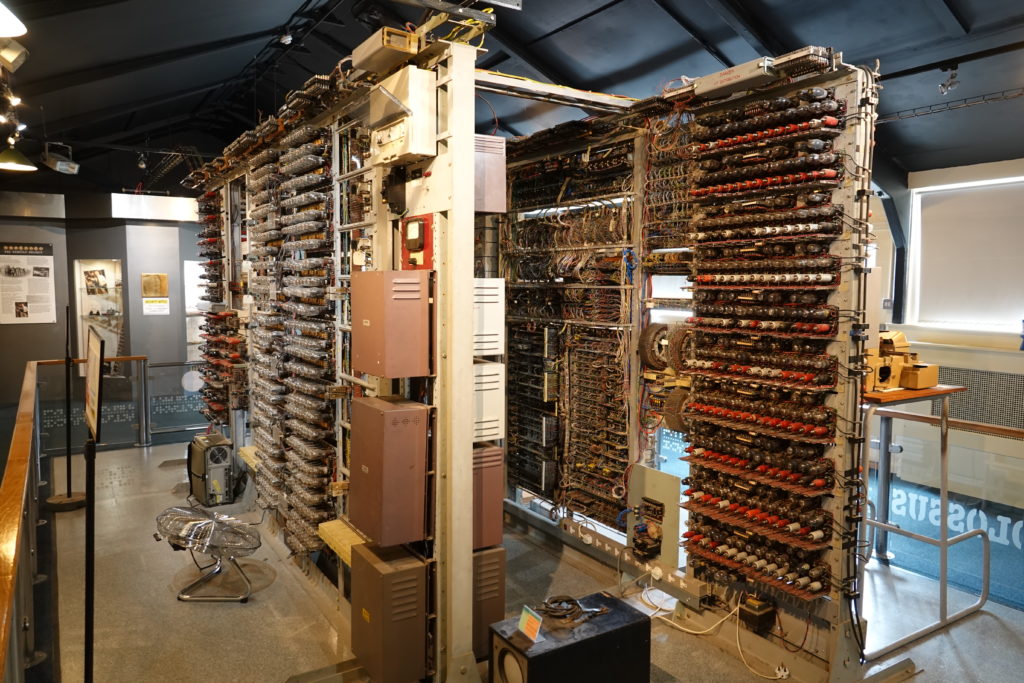

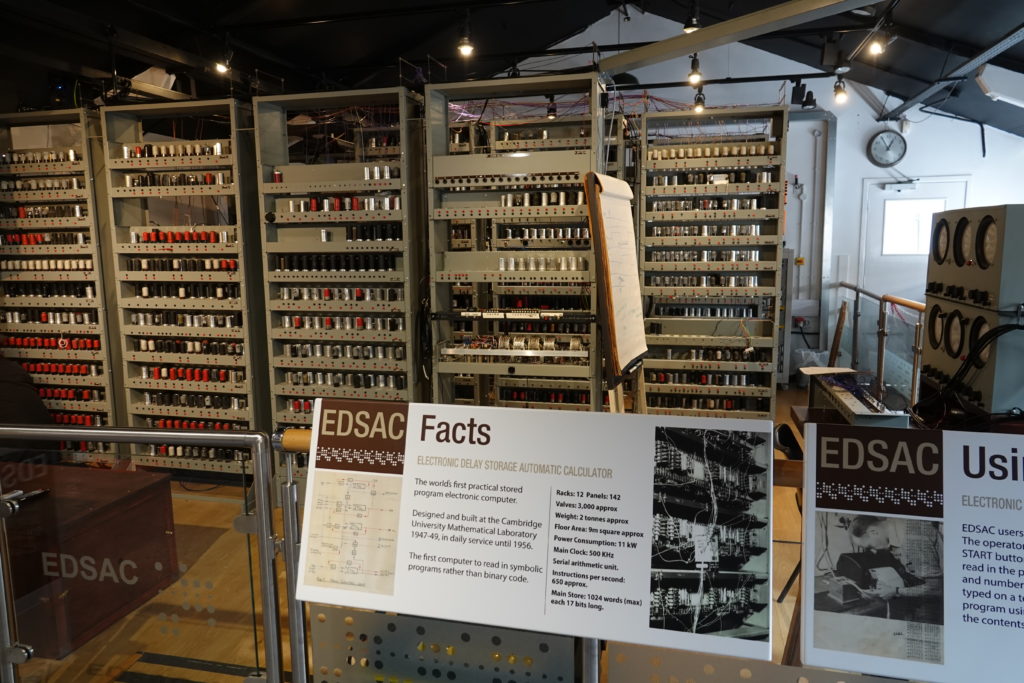

OK, they’re very special sheds. They are the sheds at Bletchley Park where the Colossus was installed, the first programmable electronic device. There are none of the original Colossuses (Colossi?) left, but there’s a working rebuild.

Let me backtrack a bit to explain why the Colossus was important. Most German military communications used the Enigma machine, which had either three or four rotors that changed the encoding after every letter. Alan Turing designed and Harold Keen built a machine called the Bombe, which had many sets of three spinning rotors to duplicate many different possible settings of the Enigma, to try and find the correct one. The design was made far more efficient by Gordon Welchman. However, that would only break the three rotor army Enigma code, and not the four rotor naval one. A more advanced version of the Bombe called the Cobra was built with sets of four rotors, but these had to spin so fast that the machine kept bursting into flames or exploding, so they ended up putting the dangerous bit on the far side of a brick wall. Performance was still less than ideal, so the British shared all the information they had with the Americans who were able to engineer a four rotor Bombe that did not explode, or if it did, it was on the far side of the Atlantic where it didn’t matter.

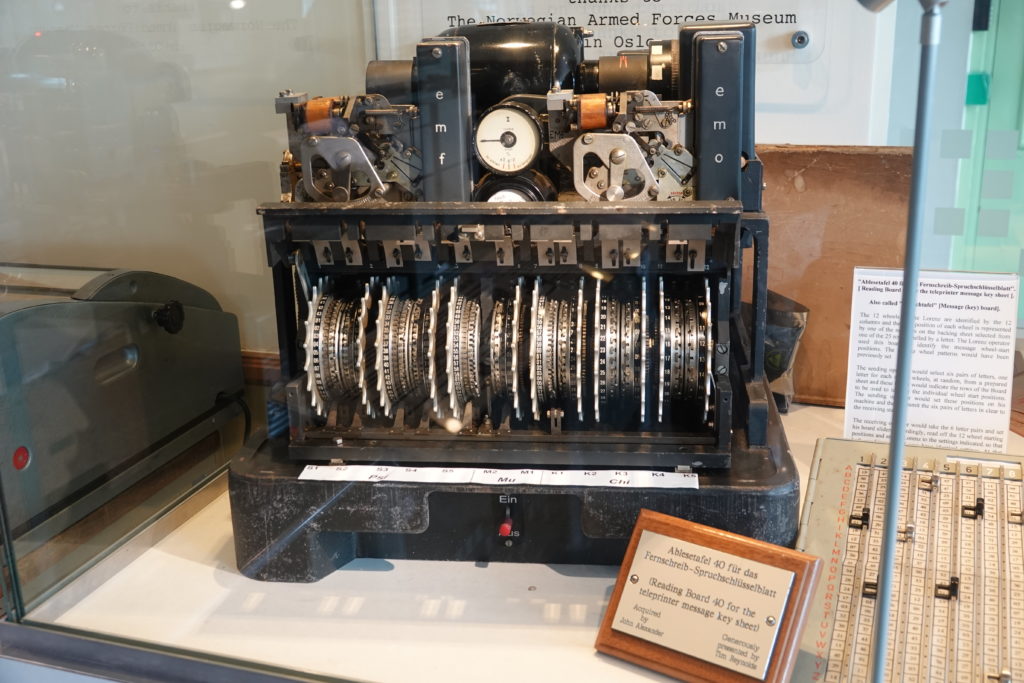

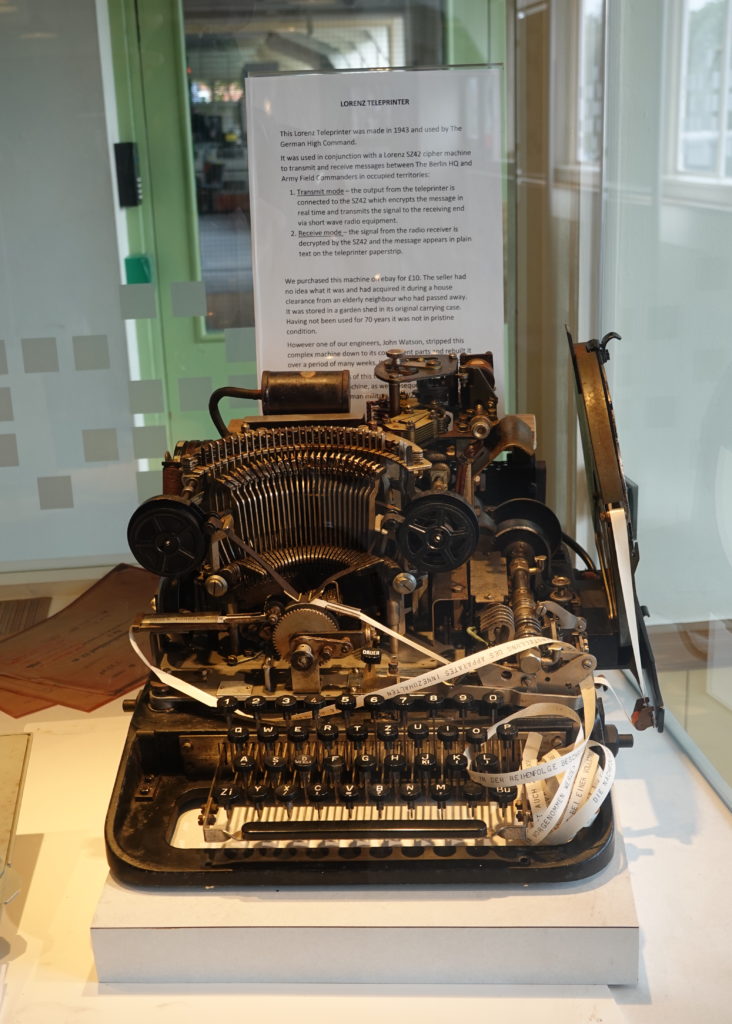

So, if four rotors was the limit of what Turing and friends could deal with, how to cope with the Lorenz code machine used by the German High Command?

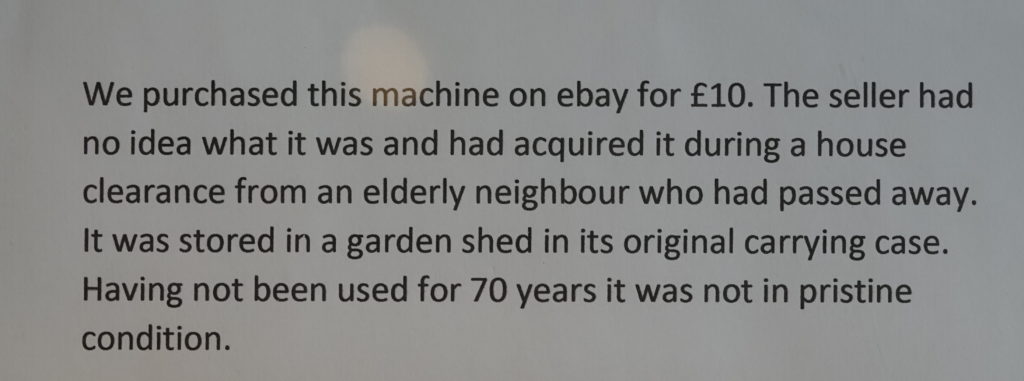

The Lorenz machine had about a dozen rotors, with different periods, some of which controlled the rotation of the other rotors. Oh, and just to make it more complicated, the code breakers at Bletchley had never seen one of the machines. They had nothing to work with except the encoded messages. The code seemed to be unbreakable, until a pair of German radio operators made a huge security error. On 30 August 1941 a long radio message, about four thousand characters, got garbled in transmission, so the recipient requested it be retransmitted. It was, but with the same initial rotor settings, and slight abbreviations in the wording.

OK, I’m going to get technical here, so you can skip this paragraph if you are not interested in cryptography. The encryption key generated by the rotors was XORed with the characters of the message (in five bit encoding) to give the encrypted message. That means if you XOR the two messages together you cancel out the encryption key and just get the two messages XORed together. This would not help if the messages were the same, but as they were slightly different, with some guesswork it was possible to get both of the original messages, and the encryption key.

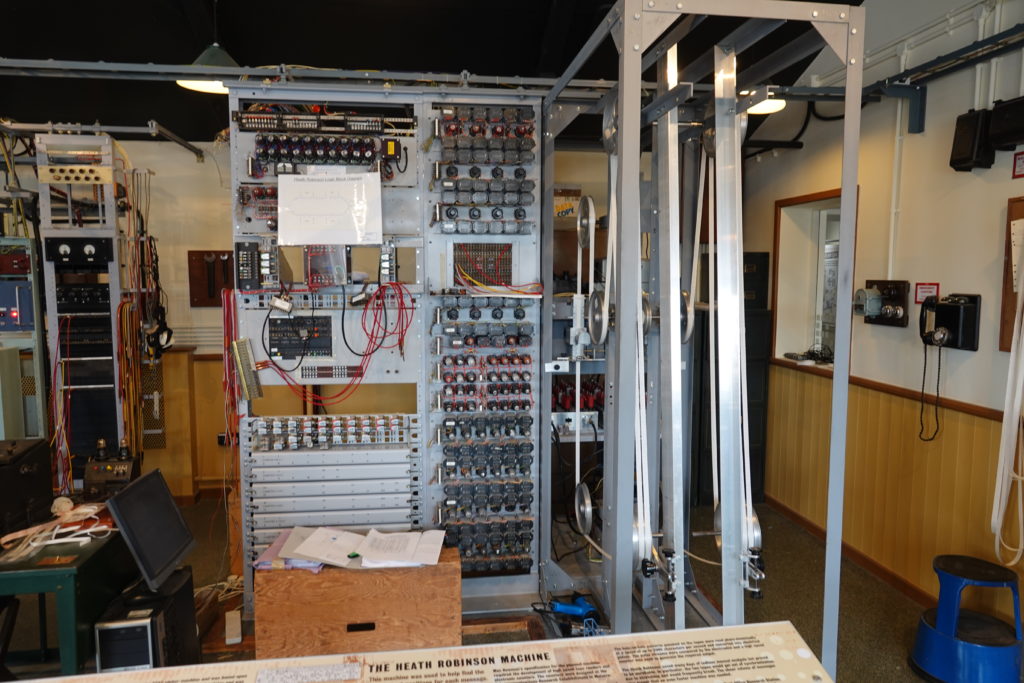

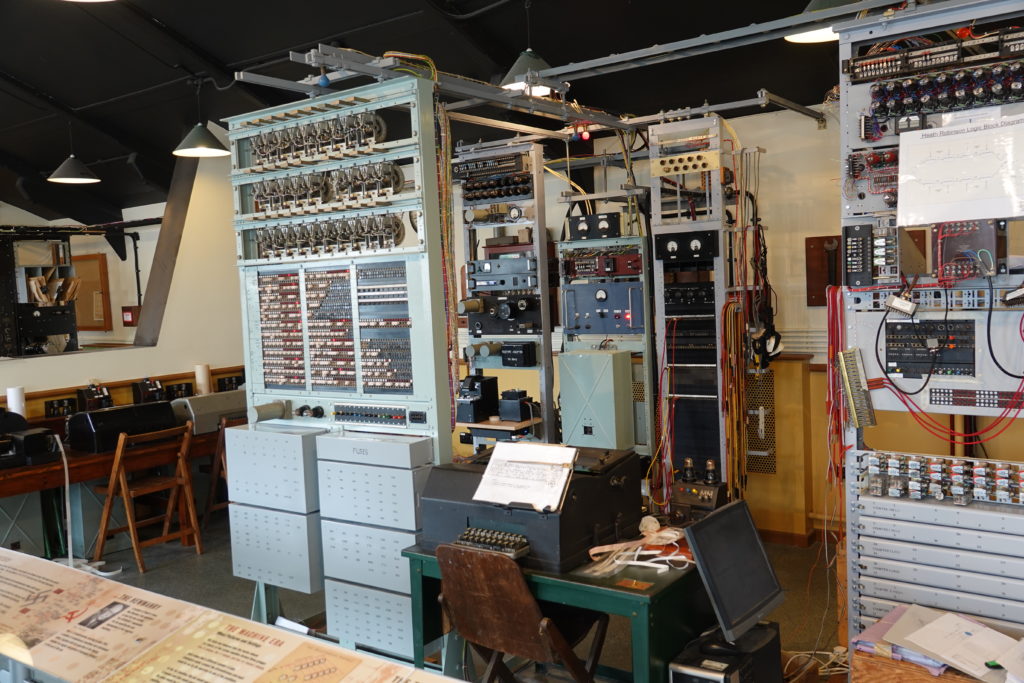

From there it only took a genius called Bill Tutte and other members of the team two months to reverse engineer the machine. That was very interesting, but still no use unless you could work out the initial rotor settings for each message. To help do this they built electro-mechanical devices called Tunny and Heath-Robinson.

Instead of the spinning rotors of the Bombe, Heath-Robinson used two loops of perforated paper tape, one for the encrypted message and one for the possible keys. However, it was hard to keep the two paper tapes in synch as they would stretch and tear at high speed.

The Post Office (which in those days in the UK was also the phone company) had built Heath-Robinson using many components used in telephone exchanges. A brilliant young Post Office engineer called Billy Flowers came up with the idea of doing away with the encryption key tape, and instead storing the values in electronic circuits controlled by valves (or tubes as they are called in the US). The bigwigs at Bletchley Park were not intersted. They thought a machine with over a thousand valves would not be reliable enough. Flowers persuaded the Post Office to build it anyway. It took eleven months to build. When the machine was complete it was taken down to Bletchley and installed in the shed where the replica now stands. When it was turned on it broke the first code in ten minutes.

Colossus was in time to decode the German High Command messages right before D-Day. Churchill’s generals knew that when the invasion was launched, the bulk of the German forces were in the Calais area rather than Normandy.

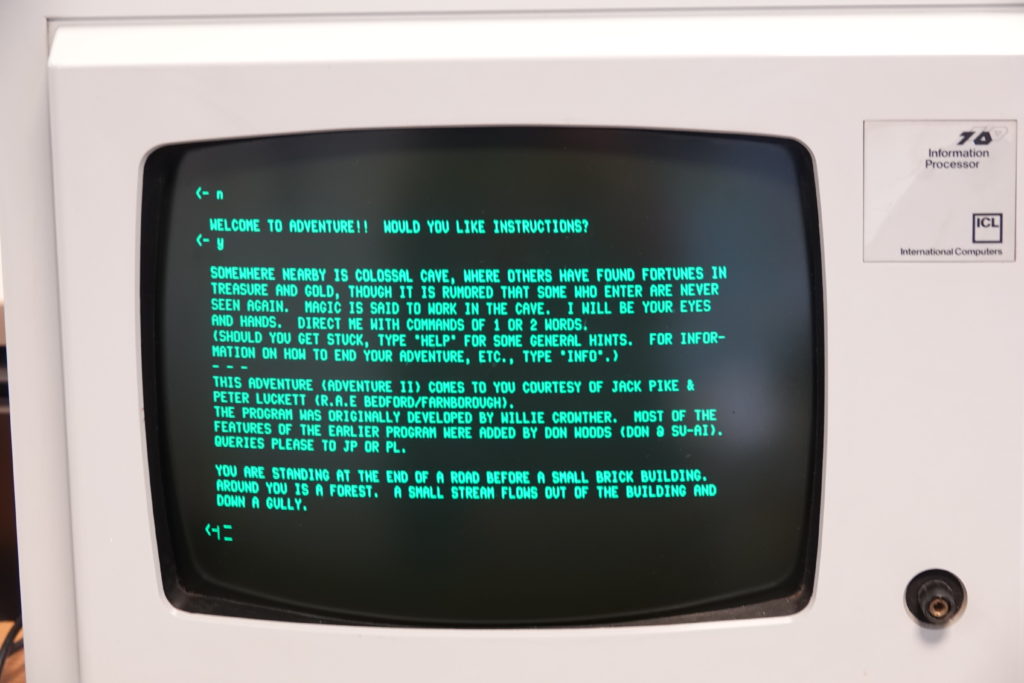

The rest of the museum alternates between slick corporate sponsored displays, and room full of jumbles of old computer gear with enthusiastic volunteers restoring and rebuilding things. The oldest working computer in the world is there. It was built in 1949-1951 to use for nuclear research.

Interestingly, it counts in base ten rather than binary, using special “Dekatron” valves with one anode and thirty cathodes, ten for adding, ten for subtracting, and ten for recording the current value. It was about as fast a human with a mechanical adding machine but it did not make mistakes and worked twenty four hours a day.

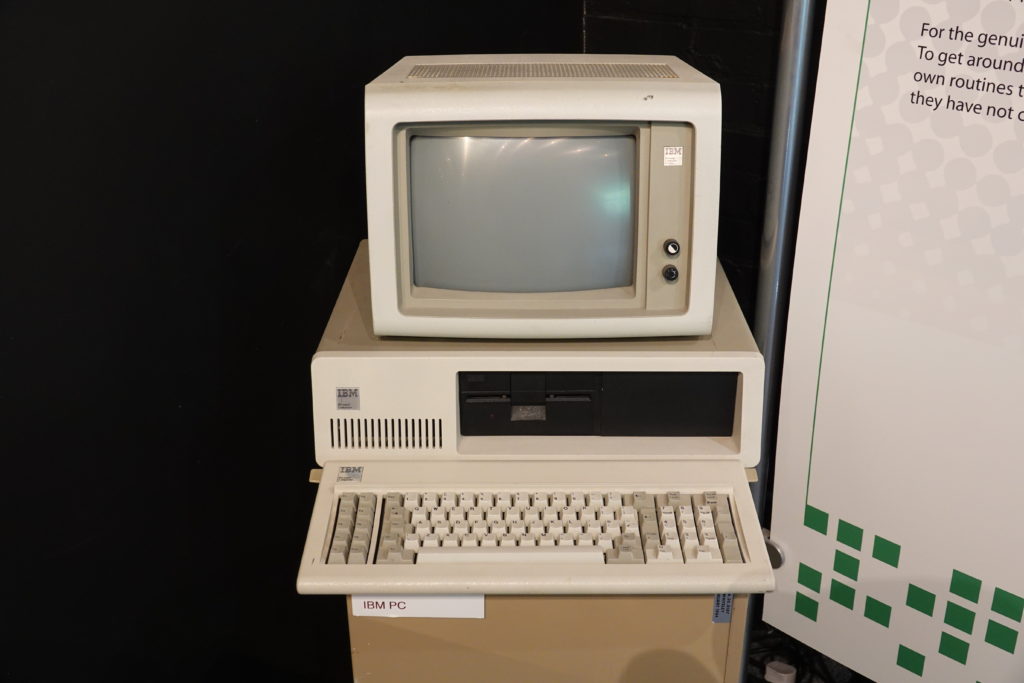

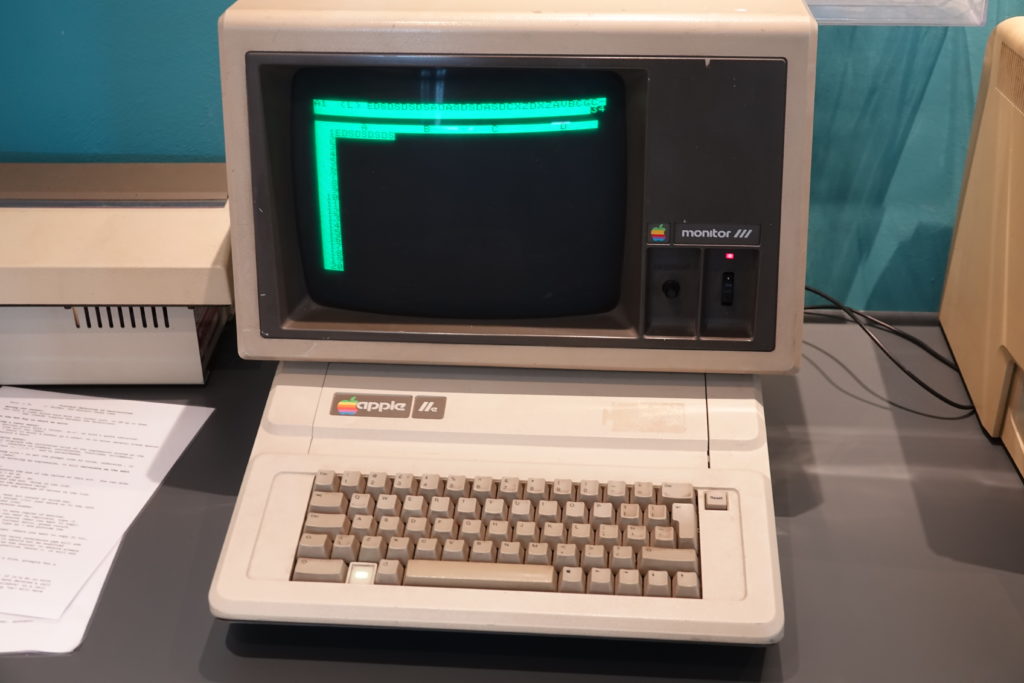

It’s nearly dinner time, so the rest of this post is going to be pictures.

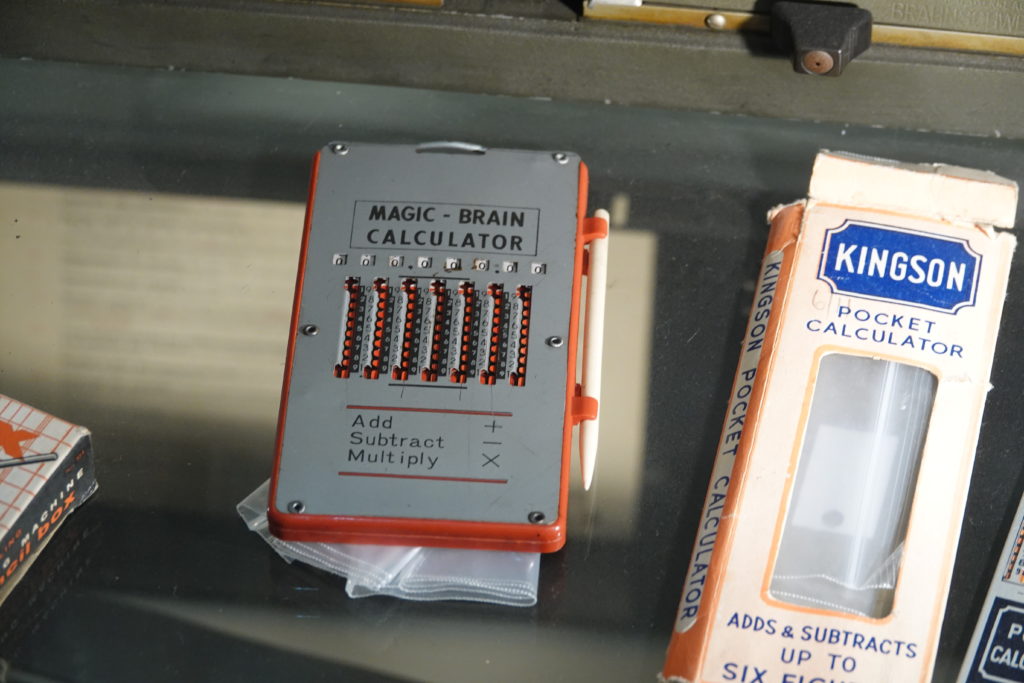

I have one of these somewhere.

I have a one of these cylindrical slide rules, too, and I can still use it.

You might think that the big advance in LGBT rights to come out of Bletchley was Turing’s pardon. However, one of the codebreakers working on the Lorenz code was a guy called Roy Jenkins. He went on to become the Home Secretary under whom homosexuality was legalized. Oh, and one of his co-workers, Peter Benenson, went on to found Amnesty International.

One thought on “The Irritation Game, Or How The Post Office Saved The Day”

Phew ! You do realise you are my favourite brother ( well actually the only one,but still favourite) . However you have a degree from Cambridge in maths, and I just about passed A level + first year university ( subsidiary subject) and failed 2nd year ( sub subject ) , so can we have some more swans,cows and carpentry in your next blog! Still love you