Secrets of the Canals

We made a later start this morning as one of the lift bridges we wanted to go through doesn’t lift during the rush hour. We passed this sculpture, called Unlock.

The artist, Thompson Dagnall, says, “Unlocked is a book holding the secrets and stories of the canals.” But really, you don’t need a bloody great sculpture to tell the secrets and stories of the canals, you just have to read this blog.

It was a short cruise to Leigh (pronounced LEE) where we stopped for groceries and then passed under Leigh bridge, moving imperceptibly from the Leigh Branch of the Leeds and Liverpool Canal onto the Bridgewater canal, which is still privately owned. Francis, the third Duke of Bridgewater inherited among other properties an estate in Lancashire with some flooded coal mines. While many young gentlemen of the 18th Century might have said, “I wonder if you can train frogs to mine for coal?” Francis’s thoughts turned to underwater canals to help drain the mine and transport the coal. This was so successful that he was left with large quantities of coal several miles from Manchester where there was a huge market for it. At the suggestion of the mine manager, John Gilbert, in 1759 he hired an up an coming engineer called James Brindley to extend his underground canal network above ground to Manchester.

Brindley went on to invent most of the technology of the canal age. Canals required an Act of Parliament to construct, and Brindley spoke before Parliament to promote the Bridgewater canal. One requirement was an aqueduct to carry the canal over the River Irwell, an idea previously unheard of in Britain. Brindley had no formal training in engineering, and did not draw detailed plans. Instead, he demonstrated the feasibility of his scheme to the Members of Parliament by carving a model of the aqueduct out of a block of cheese.

I’ll just let you think about that for a minute.

Of course only English cheese has the structural integrity for engineering purposes. Can you imagine if Thomas Edison had tried to build a phonograph out of Monterey Jack or Gustave Eiffel had tried to model his tower out of Camembert? It was probably a proud wheel of Cheddar that Brindley used, with Red Leicester to line the canal, and Stilton and Sage Derby for the decorative elements. Sadly, cheese does not have the same durability as Brindley’s other works, so we no longer have this gastroengineering masterpiece. We just have to make do with the hundreds of miles of canals that Brindley created instead.

After lunch we moved another few miles to the Astley Green to visit the Lancashire Mining Museum.

The fake coal mine is about the most museumy bit. The rest of it is the remains of a genuine colliery where you can wander around the above ground bits with little regard to health and safety regulations.

The headgear shown here is rusting and needs to be cleaned and painted or it will have to be demolished. The cost of repairs and preservation is half a million pounds, which the museum doesn’t have, so if anyone reading this is interested in preserving Lancashire’s industrial heritage feel free to chip in.

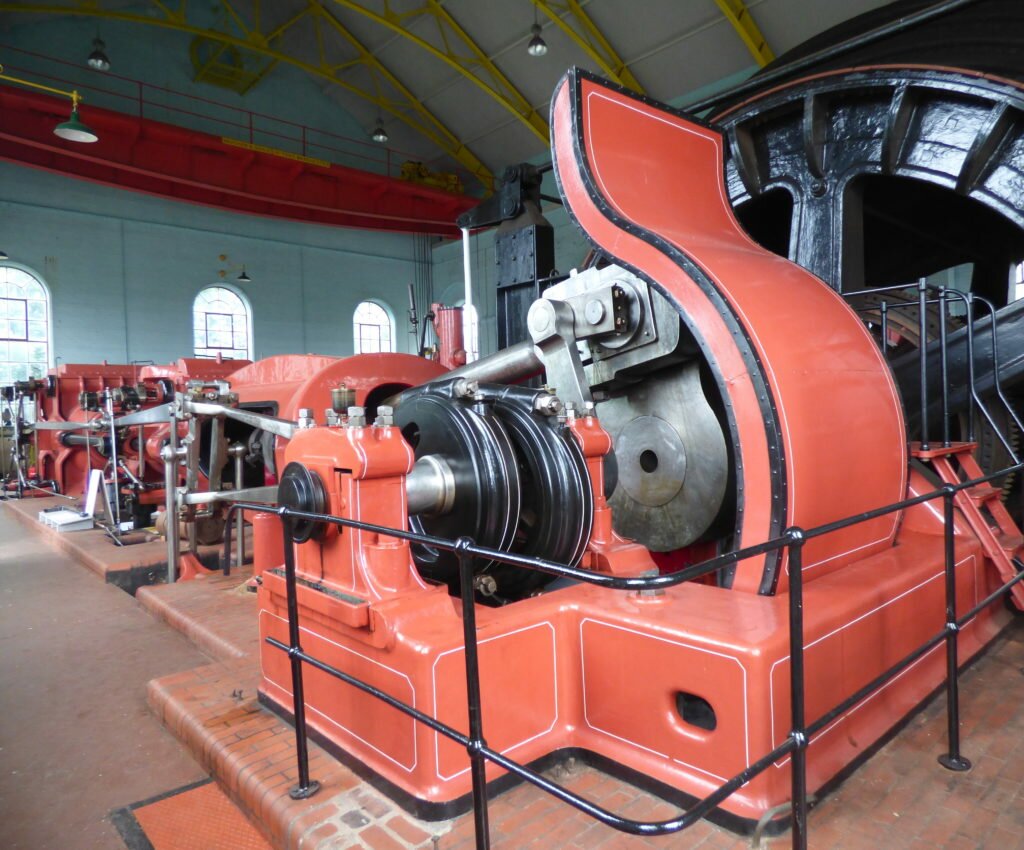

The headgear was the structure used to haul coal out of the mine, and also get the miners in and out. Of course, you needed an enormous engine to power that.

The winding engine is a 3,300 horsepower monster built in 1912.

Here’s the engine room from the outside.

The still run it from time to time, but using compressed air rather than steam.

We chatted to one of the volunteers, who worked as an apprentice engineer on that engine back in the day. “Me dad were down the mine fifty years till the coal dust killed ‘im,” he tells us without bitterness. Mining was a way of life, and conditions in the 20th century, though terrible, were not as bad as the 18th or 19th when children as young as eight could be working down the mine for twelve hour shifts six days a week, facing death from suffocation, explosion, or collapse. Not that the risks went away in the 20th century. In 1939 five men were killed in an underground explosion at this pit, over a mile away from the pit head. Here’s the monument to them made by a blacksmith working on site.

Astley Green village green is about the size of two tennis courts, and has a sign up forbidding horse riding. There is a story there methinks.

Did someone try to stage a tiny gymkhana for shetland ponies? Or set up a retirement home for pit ponies?