Internal Combustion

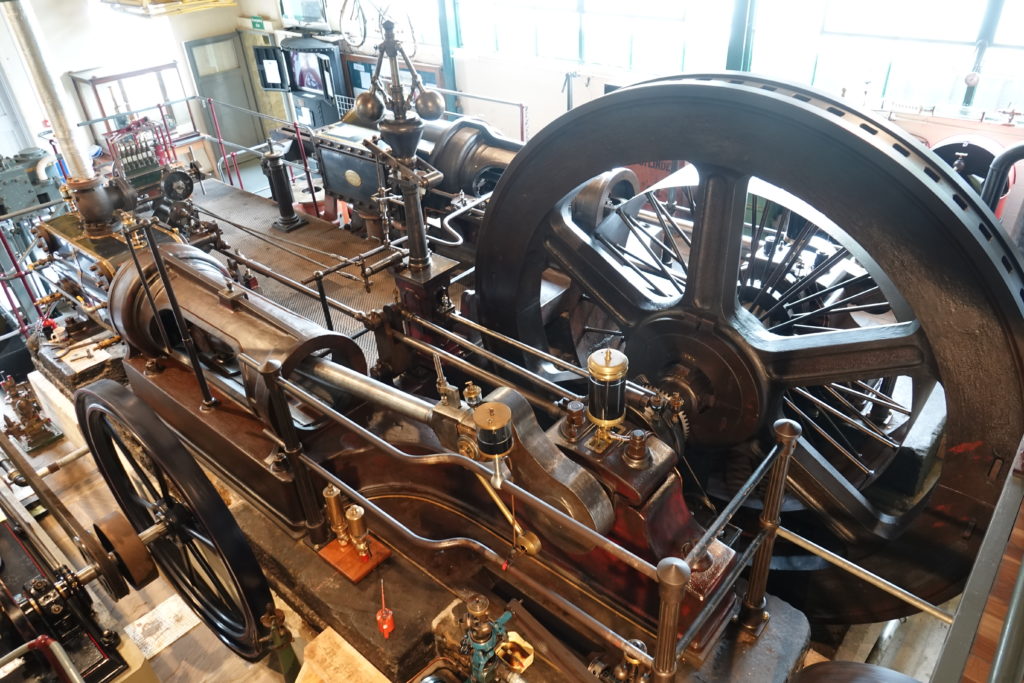

Steam engines are great, and they have a room full of them at the Anson Engine Museum…

… many of them today chugging away with steam from a natural gas boiler. But they are only about 10% efficient at turning the energy in their fuel into usable work. By the mid 19th century inventors were wondering if you could get more efficiency by burning the fuel inside the engine rather than using it to generate steam pressure.

In 1858, Belgian Jean Joseph Étienne Lenoir designed an engine in which fuel was burned inside the cylinder, powering a piston. Sadly this engine was even less efficient than a steam engine, converting only 4% of the energy from the fuel into useful work. However, it had the advantage that it could be turned on and off a lot faster than a steam engine, so Lenoir engines were a limited commercial success.

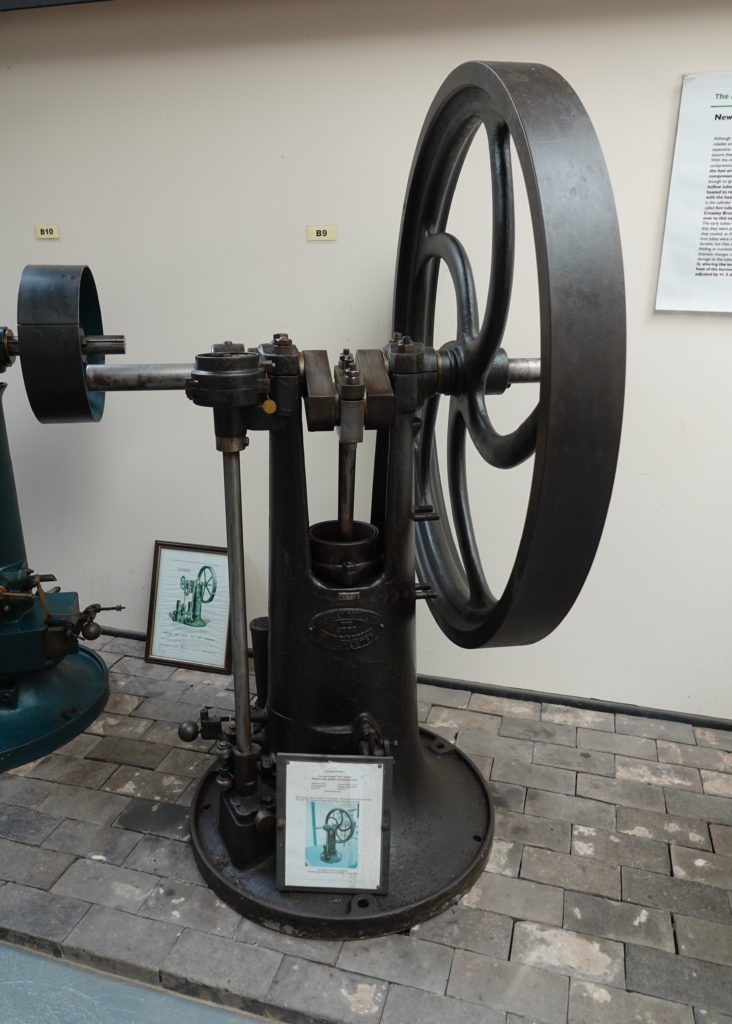

Other engineers worked on improving the design. This is the only surviving engine designed by Pierre Hugon.

It is a half horsepower engine built in 1867.

The Lenoir engine inspired German inventor Nikolaus August Otto to wonder if the engines could be made more efficient by compressing the mixture of fuel and air before igniting it. He and his partners experimented with both two stroke and four stroke engines. A four stroke engine works like this

- Induction – piston goes out sucking fuel and air into the cylinder

- Compression – piston goes in compressing the fuel and air

- Explosion – fuel and air burn, pushing the piston out

- Exhaust – piston goes in pushing the waste gasses out of the cylinder

… or Suck, Squeeze, Bang, Blow for short.

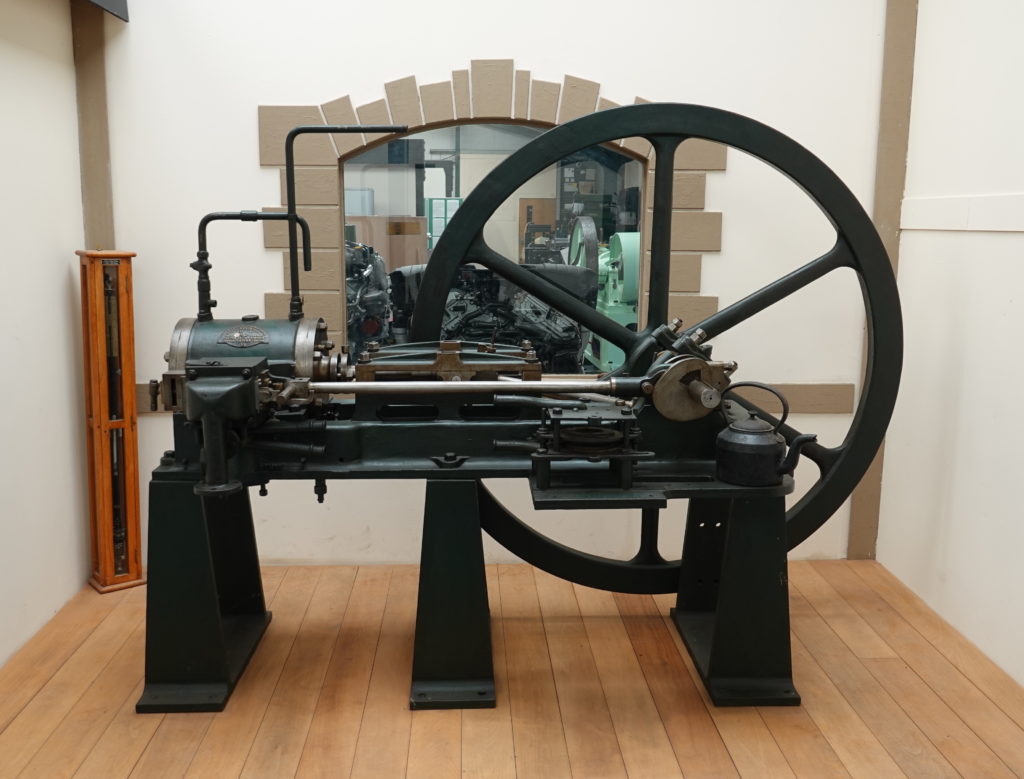

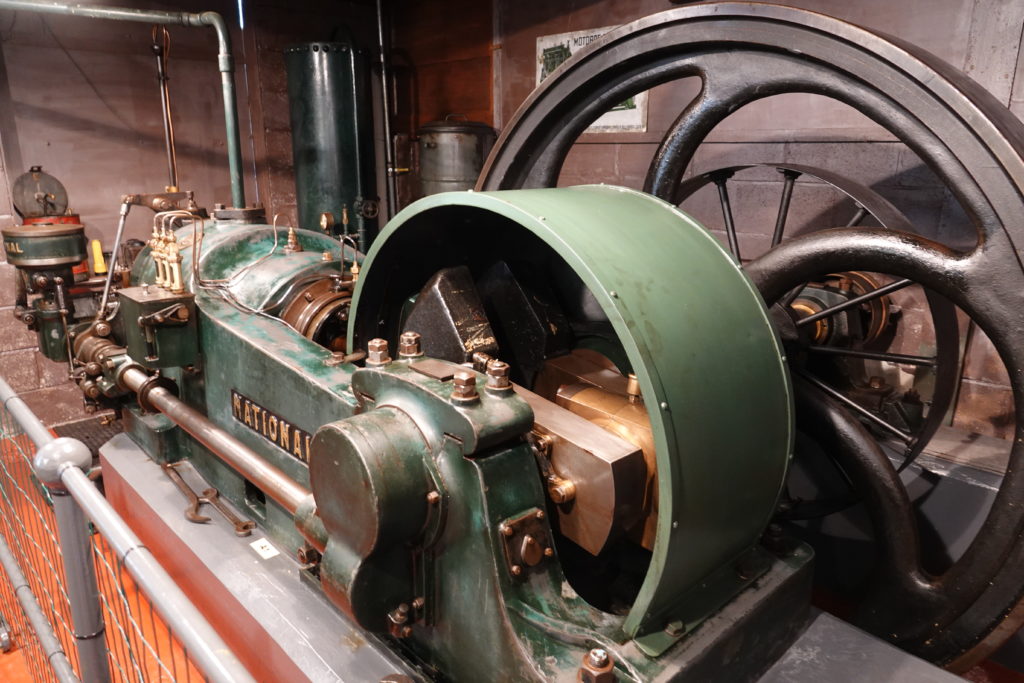

Here is an Otto engine built in 1898 under license in Manchester.

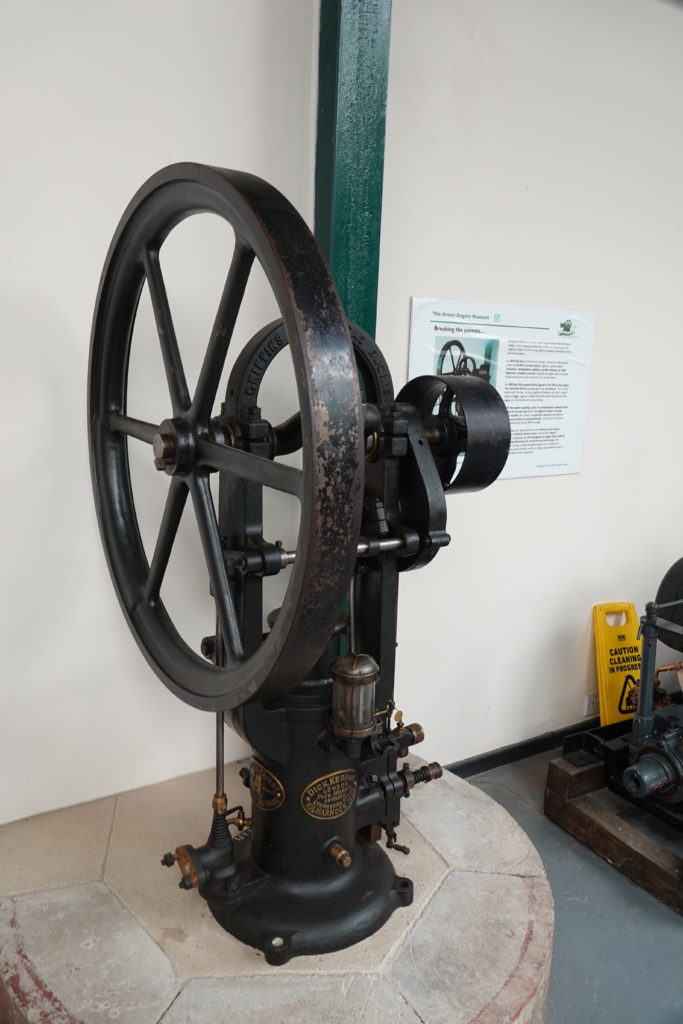

Otto’s patent on the four stroke engine was an obstacle to other manufacturers. One even built this six stroke engine, in which two strokes did nothing, in order to circumvent the patent.

One problem with internal combustion engines was igniting the fuel. A pilot light or a spark plug might be used. One engine in the collection had the problem that the pilot light was blown out every cycle, so there had to be another pilot light to relight the pilot light. Early spark plugs were temperamental and there was a separate electrical system to maintain. By the 1890s German engineer Rudolf Christian Karl Diesel was working on engines in which the heat generated by compressing air was enough to ignite the fuel, which was added at the end of the compression.

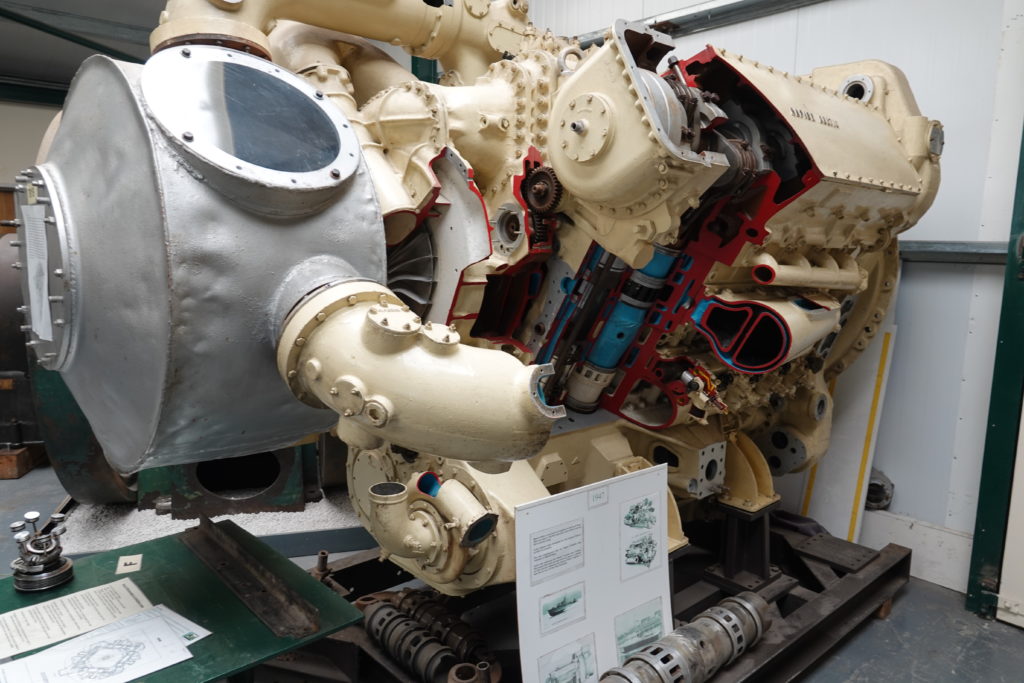

Diesel’s experiments with high pressure engines did not go entirely smoothly. One of them exploded putting him in hospital for months, and in another the pressure gauge blew off narrowly missing him. However, by 1897 he had a working engine design. This is the third diesel engine ever made, and the first made in the UK.

A couple of the engineers who worked for Otto went on to form their own engine company. One of them was called Daimler.

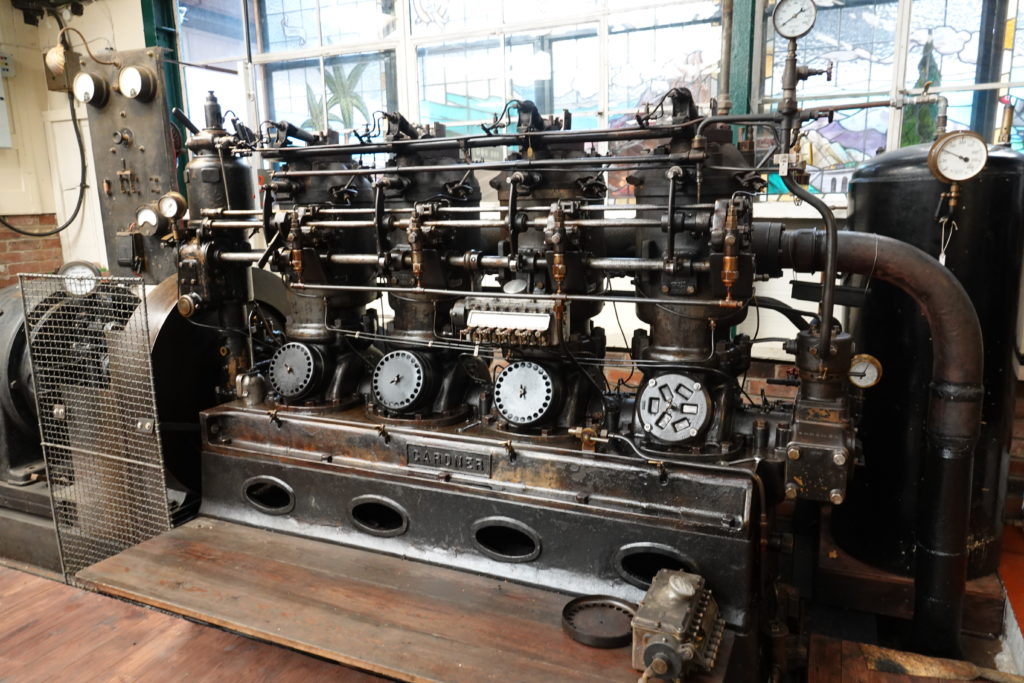

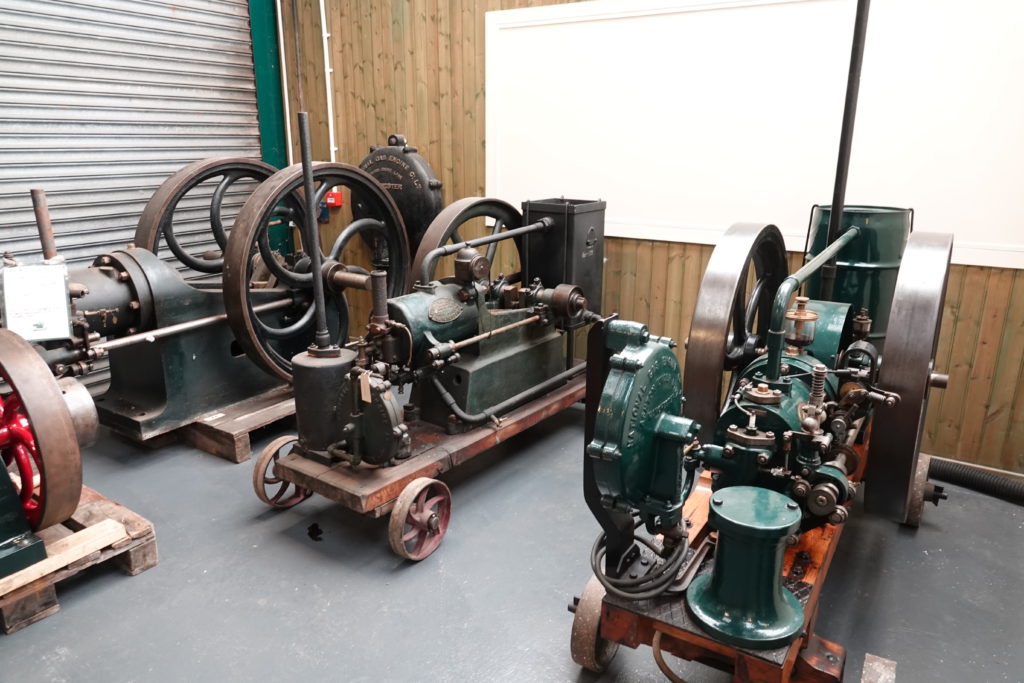

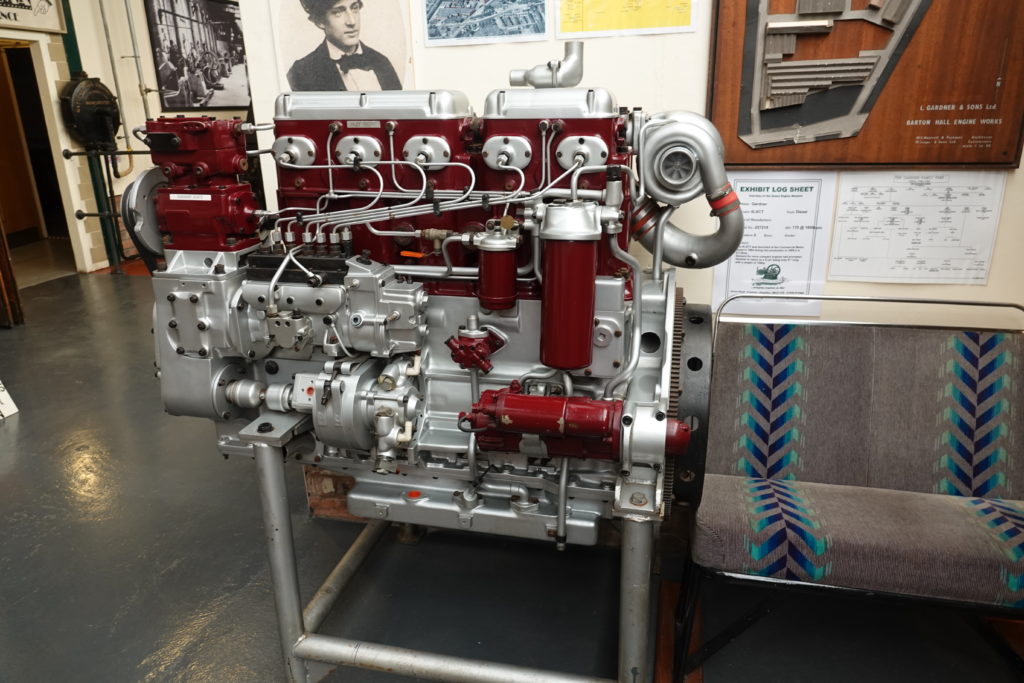

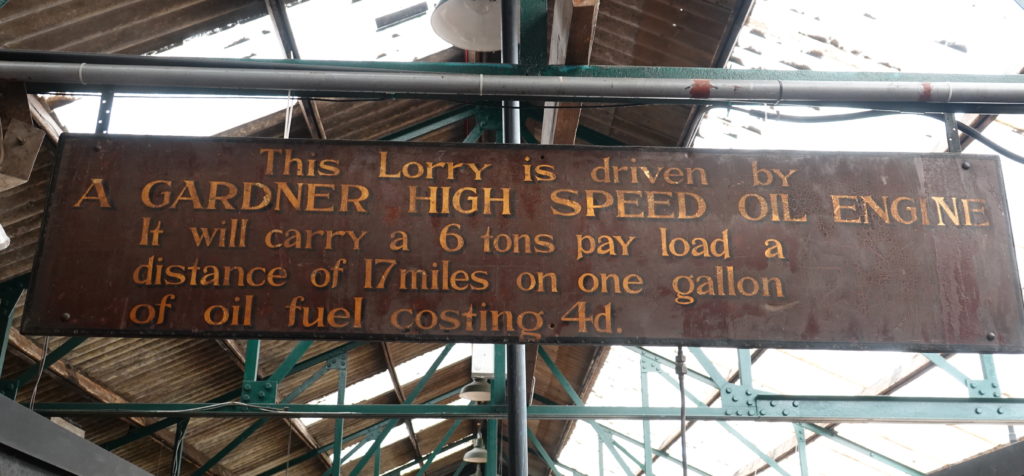

Here’s some more engine pictures from the museum. Most of them are in working order and quite a few of them were running today. If there is such a thing as dieselpunk, this is the place for it.

Yes, that is a bus seat.

There’s also a traditional crafts area, with a smithy and a totally non mechanized wood shop.

Fuel costing four pence a gallon. Now that’s a museum piece.

One thought on “Internal Combustion”

I once had a neighbour (ex salesman , say no more!), who on buying his first diesel car ,explained to me that it was a very high compression version for increased performance ! I didn’t bother to tell him that if they charged

him for spark plugs on his next service he was being ripped off !! ( apologies to all you wonderful salesmen!). Ant