Bristol

Today we rode an Isambard Kingdom Brunel railway to see an Isambard Kingdom Brunel ship. Except that Brunel’s railway, the original Great Western Railway, was better than the current one. He was a good enough engineer to know that trains were more stable and can corner faster if you put the rails further apart. His GWR had the rails six feet apart, while the other railways in the country placed the rails four and a half feet apart. That was the width that the rail used for carts that were dragged out of mines by pit ponies used, and no other railway engineer had the insight to see further than a horse’s ass.

Sadly the inferior technology won out as Brunel was a better engineer than he was a businessman. The GWR was forced to rip up their wide rails and replace them with narrow ones to be compatible with the rest of the network. It doesn’t matter any more that VHS beat Betamax, but railway engineers are still bitter over the fact that the GWR width did not become the standard.

The train was six minutes late. Maybe it could have kept on schedule if the rails had been further apart.

This was what I wanted to see.

The SS Great Britain, the first iron hulled propeller driven steamship. Launched in 1843, she could cross the Atlantic in 14 days. Brunel originally envisioned the ship as a wooden hulled paddle steamer, but realized he could get greater size and strength from an iron hull, and when a small boat with the newly invented propeller drive visited Bristol, he was impressed by the possibilities and changed the design again.

You may have noticed that in the first picture the ship seems to be in the water, but in the second, we are underneath looking up. The ship is actually in the dry dock where it was built, with a layer of plate glass and then a few inches of water to give the illusion that it is still afloat. To prevent the fragile hull from corroding further, it is kept in arid conditions by a giant air conditioner, and lots of ductwork.

The ship went through a number of changes. When the engine became obsolete in 1881 it was taken out and the Great Britain converted to a sailing ship. When the age of sail passed she was used as a warehouse in the Falkland Islands. She was finally abandoned in 1937. Though there was a movement then to preserve her, World War II intervened. There she lay until 1970, when there was another move to preserve her. Sir Jack Hayward, one of the owners of the Grand Bahama Port Authority, put up the money to have her remains loaded onto a barge and towed back to the dry dock in Bristol where she was built.

There’s been a fair bit of restoration work done since then. While the hull is beyond repair and she will never float again, the promenade deck and the dining room are close to their original condition.

The plumbing is also resplendent.

Why yes, that is indeed a Crapper.

Thomas Crapper, to be specific, but he was an engineer in an entirely different field than Brunel.

Just down the way is an modern reconstruction of what John Cabot’s ship Matthew might have looked like.

Cabot sailed to Newfoundland in 1497, a few years after Columbus visited the Bahamas. Cabot was the first European to visit North America since the Vikings, apart possibly from the Bristolian cod fisherman who had been going there for years but not telling anyone about it so that the place would not get fished out. In Bristol they believe that America was not named for Amerigo Vespucci, but for Richard Amerike, owner of the Matthew and wealthy fish merchant.

Anyway, Cabot spilled the beans to Henry VII. Remember him? Probably not, he was the boring one. Henry VII was so impressed he gave Cabot an award of ten pounds plus a pension of twenty pounds a year, and sent him off to do some more exploring. Cabot never came back from the second expedition, so Henry never had to pay out the pension. Good with money, Henry VII was.

By the way, not only were the Newfoundland cod pretty much fished out, but when they came to build a replica of the Matthew, there were no oak trees in England big enough to make the keel any more, so they had to import African hardwood.

The other thing to do in Bristol is go looking for Banksy’s paintings.

This one is two stories up a wall, so it was really quite hard to vandalize, but somebody managed it, probably with paint filled balloons. Google “Banksy Naked Man” if you want to see what it looked like before the blue paint additions.

Can you take another cathedral? I wasn’t sure I could, but there was Bristol Cathedral on the way back from the Banksy.

Parts of it are 13th Century, much of it is 19th Century, and you can’t see the join.

The stained glass window are a bit random. There are several devoted to people who did good things for Bristol during World War II.

Nurses deserve the stained glass, they do a lot more good than saints. But then there are famous sea captains.

Francis Drake, Lord Nelson, Robert Blake, and Walter Raleigh. You’ve probably never heard of Robert Blake because he was the leader of the parliamentary navy during the Civil War, and after the Restoration he became an unperson. These were all great sailors, but not always the most pious of men. Raleigh for example, introduced tobacco to England was was executed for treason.

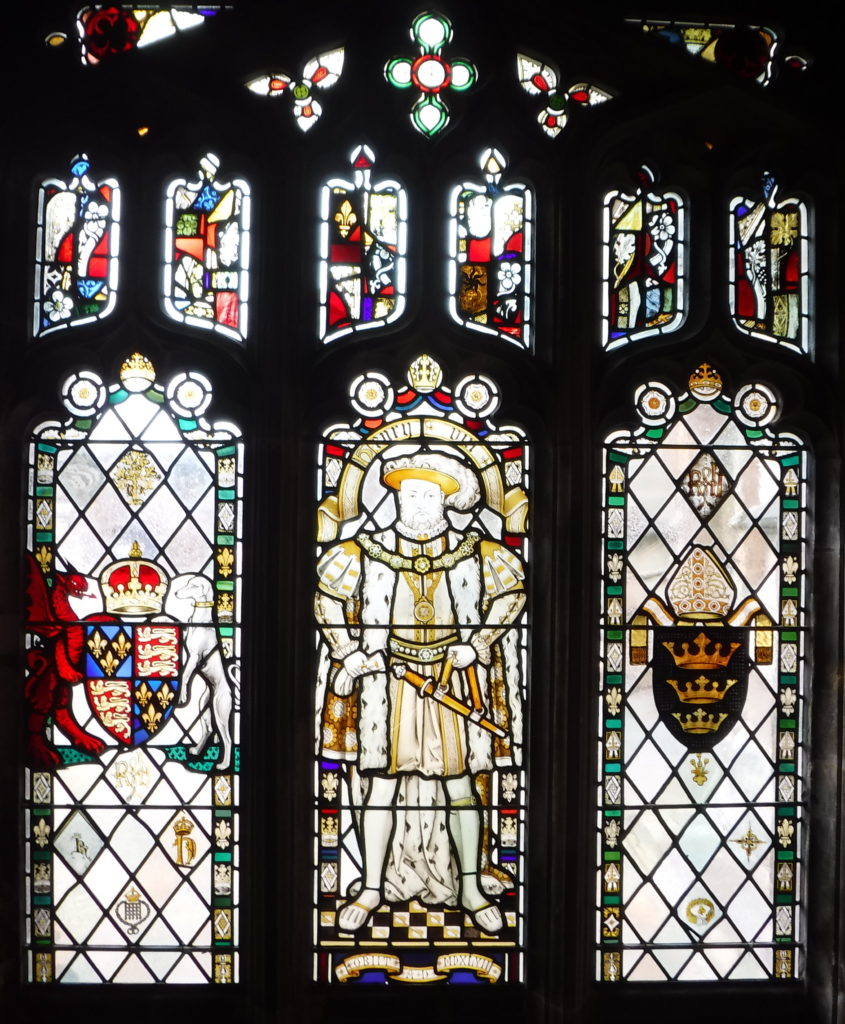

Out in the cloisters is this guy.

Henry VIII. Of course you remember him, he was much more interesting than his dad.

Finally, I should mention that the SS Great Britain has a battle swan on the stern, because we haven’t had enough dangerous waterfowl lately.